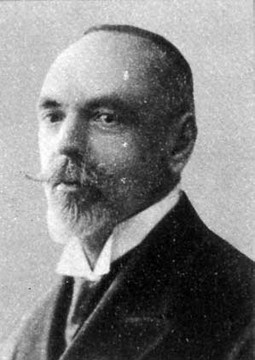

Béla Vikár 1909

Béla Vikár, who had translated the Kalevala into Hungarian in 1909, began his celebratory speech at the Kalevala-gala held by the Kalevala Society in 1928 by comparing the fates of the sister nations during the past decades. He reminisced about his previous visit to Finland, 23 years earlier, when the independent Hungary had been living in blooming prosperity whereas “the sky in Finland was still overcast with dark clouds”. By the year 1928 the situation was totally opposite. Hungary had become a “crippled, sickly figure”, whereas “The Finnish lion had lifted its head and attained its well-deserved freedom with bravery”.

In his speech, Béla Vikár detailed all the stages that led him to become a translator of the Kalevala.

His father had been a teacher of Hungarian language and literature and, later on, he also became a Calvinist priest “in the most remote villages in Hungary”. Little Béla started to write at a young age and when he was in high school, he already won several poetry competitions. However, he says that his own career as a poet ended because of a moment of shame that he experienced at a university seminar. After this he “converted into a translator”.

During his professional career, Béla Vikár first worked at the Hungarian parliament as a stenographer and he later became the head of the stenography agency, A. O. Väisänen writes in the eulogy in the yearbook of the Kalevala Society 25–26. However, he was also, and specifically, a great friend and promoter of poetry and literature.

Old Man Budenz’ wine club

Vikár studied at the University of Budapest where [József] “Ukko/Old Man” Budenz was the professor of Finno-Ugric languages. Budenz had a great influence on Vikár’s career.

“I was a most devout listener at his lectures. The Finnish language – not because it is related, but because of its beauty – had an enormous appeal to me. The museum park saw me in the spring as early as 6 o’clock in the morning holding a copy of Budenz’ scientific Finnish grammar.”

Professor Budenz loved poetry and he took Béla Vikár to his private club that held weekly meetings around a table with wine and beer in a restaurant in Buda. He encouraged, even pressured, Vikár to translate the Kalevala: the epic had to be re-translated “as poetically as it deserves”. Budenz even arranged a whole Kalevala semester in order to inspire and coach Vikár.

“Finally, I agreed, although I was still scared of Dr Barna, that he would hate me every week and stop me from becoming a writer. Of course, there was no reason for this. But I, an inexperienced young man, could not criticize the thoughts of the bearded old man.”

The intimidating professor Gyulai

Vikár was even more scared of the head of the Kisfaludy association, the professor of Hungarian literature Pál Gyulai. Gyulai had “a dominant character, he was a strict critic, an intimidating complainant who criticised even the works of the most eminent authors”. Gyulai took Vikár under close scrutiny. Besides their meetings, Vikár was also invited to dinner and the poised beauties made the clumsy boy from the countryside anxious. The young man was, for example, concerned that he would fall in love with either one of the daughters of this marvellous man and the future reviewer of the Kalevala translation.

Professor Gyulai evaluated the test translations by the young Vikár positively and his support was a definite prerequisite for the success of the whole project. Gyulai told Vikár to recite the Joukahainen poems at the Kisfaludy association where the “father of the translators himself”, Károly Szász, stood up and held an impassioned speech of the importance to gather funding for the young translator.

But on what meter?

In his translation work, Vikár was worried whether the translation, in fact, would correspond to the Kalevala when regarding the poetic meter or would it remind lyrical Hungarian folk songs too much. In 1889, he decided to travel to Sortavala to meet the folk singers that were still alive. The journey was a combined work trip and honeymoon. When he travelled through St. Petersburg, he tried to ask the czar’s court painter, Michael Zichy, to illustrate the next master piece.

In Sortavala, Vikár had the opportunity to listen to, among others, Pedre Shemeikka, together with his friend Oskar Relander.

“It was not until I, myself, heard how the old Finnish narrative poetry was performed in Karelia, and later also in schools by young people, in other parts of Finland, that I have been able to settle for the presentations and examples that I had the opportunity to read in Genez’ book and hear from him. I discussed this often with him and others as well – Ahquist and other scientists.”

Based on what Béla Vikár had heard and learned, he had to conclude that the poetic meter that he had used, in fact, did not work well, which was something he also had suspected himself.

“I was convinced that the first part of my translation, that already was finalised, and although it was accepted in our country, it did not any longer satisfy the requirements of my conscience. I have to abandon it; I have to re-write it. It would have been better to visit Finland and have these experiences before we started translating the texts.”

Transylvania teaches

Béla Vikár followed the voice of his academic conscience and did a translation that was groundbreaking in Hungary: during the summers 1893–1900 he went to stay with the Hungarians in Transylvania for weeks. He took a phonograph with him and he collected their songs in order to find the correct poetic format for his translation of the Kalevala. Consequently, Vikár gathered data from the field and he could return to it in peace when he was back home again, “without disrupting the pronunciation and the poetic structure”. Among others, composers Béla Bartók and Zoltán Kodály were later inspired by Vikár’s phonograph method and used it in their own extensive work when collecting Hungarian folk melodies.

The Hungarians in Transylvania (or the Székelys as Vikár calls them) and their epic narrative poetry influenced Vikár’s choices when he translated the poetic language of the Kalevala into Hungarian. “The lyrical voice was reduced and the epic motion was predominant”, which was an exceptional solution. “At first, my Kalevala poems seemed odd in all parts of Hungary, except for in the Székelys’ region, which is the place where I had received the pattern for them. Here, all people read and listened to it with admiration.” The poems were published in the leading monthly magazine in Transylvania and people came to listen to them to reading sessions that were organised in, for example, a health spa.

Béla Vikár’s translation of the Kalevala was very popular in Hungary: it was known even before the complete translation was published.

“For example, Magyar Könyvtár (a library in Hungary) printed the Lemminkäinen poems separately. As it was very affordable and available everywhere, in tobacco stores etc., the name of the new translation was soon spread all over the country. At the same time, a longer series of poems from the Kalevala was published in a weekly magazine that was popular among the commoners and also as a separate edition that was sold. Consequently, the Hungarian people learned to know the epic, at least to some extent, well in advance before the whole book had been published by the Academy of Science.

Akseli Gallen-Kallela was a friend of Vikár’s and he was, at the same time, in Budapest and he created a “wonderful cover picture for the book and also some other drawings”.

Béla Vikár managed to negotiate a larger monetary compensation for the translation than usual, 80 crowns for 16 pages. 20 crowns would have been the usual compensation. “My Kalevala is not a Barnevala, as the translation by doctor Barnan was jokingly called, but it is a Hungarian Kalevala, which has needed more than 20 years to become what it was today.” The investment by the Academy was worth it, since the edition was sold out quickly, even though the book was expensive. It had a huge impact, particularly, on Hungarian poets, who started to study and utilise, not only the Kalevala, but also Hungarian narrative poetry in their production.

The ten years long top tier project by Béla Vikár – the translation, adaptation, finalisation and triumph of the Kalevala – happened during the blossoming years right before the world wars. During the first world war everything changed, when the Hungarian regions were divided among the neighbouring countries. Czechoslovakia got Slovakia, Romania got Transylvania and Yugoslavia got the southern part of the country. Vikár summarised in his speech in 1928:

“Our heavy fate took from us the majority of the readers of the Kalevala: Twenty-seven of the most civilized cities in the old Hungary. We have not only lost 2/3 of our land and our people, but also 2/3 of the soul of our people. In this situation, we now only have the prairie and we have been put in the same situation as the Indians in North America, and thus, there is no hope whatsoever that a new edition would be possible. From now on, you can only find the Hungarian Kalevala in the reading halls in libraries; the individuals who acquired it before the world war are now, without almost any exceptions, subjects of a foreign and, also now, hostile power. Thus, the influence of the Kalevala decreases in the small, spiritually suppressed Hungary.”

Bertalan Korompay writes in his article ”Béla Vikárin muisto” (in English: In remembrance of Béla Vikár) in the yearbook of the Kalevala Society 36 that Vikár died in 1945 exhausted by the strains of the second world. However, before he died Béla Vikár was able to see the updated, glorious edition of his Kalevala. It was published by the La Fontaine association, that he had founded himself, in the Jubilee year of the Kalevala in 1935 and it was illustrated by Akseli Gallen-Kallela’s pictures from the Koru-Kalevala. After this, there were three more re-prints of Vikár’s translation: 1940, 1943 and 1950.

When Béla Vikár had died, a room was dedicated to him at the University of Debrecen and a large part of his books was preserved here. The version of the Kalevala in which Vikár had stenographed his translation in the margins is also preserved. (See Weöres, yearbook of the Kalevala Society 38.)

Béla Vikár: ”Kalevala-käännökseni vaiheista. Kalevalaseuran Kalevala-juhlassa 28.2.1928 pidetty esitelmä” – Kalevalaseuran vuosikirja 9. Helsinki: WSOY. 1929.