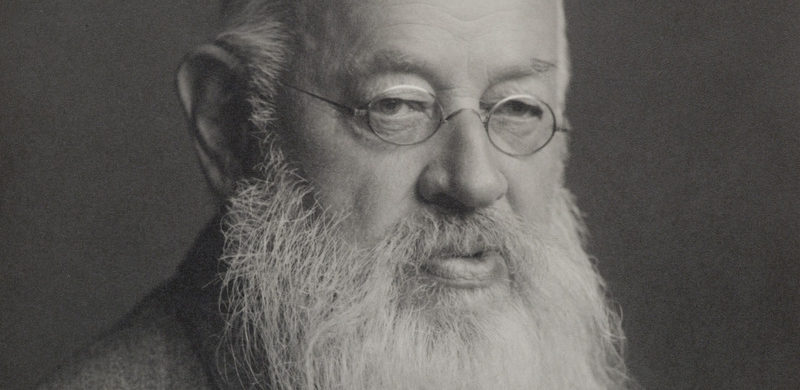

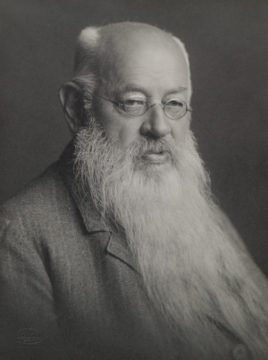

Josef Holeček 1894–1895

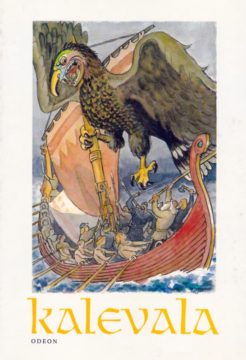

Josef Holeček (1853–1929) is the only one who has translated the Kalevala into Czech, but, by no means, the only Czech intellectual who at the end of the 19th century, became interested in the Finnish language and culture as well as in the Fenno-Ugric language history. Notable predecessors of Holeček were, for example, Johan Amos Comenius (1592–1670), who was an expert in pedagogical philosophy and a theologian and Josef Dobrovský (1753–1829), who was a researcher of linguistics. However, in the Czech cultural sphere Holeček was the first one to take on this linguistically important challenge to become a conveyor of Finnish and Czech culture. At that time, Holeček and his friends saw that there was a great need to open up new cultural views and, in particular, to promote connections to other small countries that existed as a part of powerful states.

Folk poetry played the most important part in Holeček’s project, since, according to him, the most authentic and original verbal power was embodied in folk poetry. Holeček was well equipped to translate the worlds of the Kalevala and the Kanteletar (he translated about a third of the poems): he came from a rural part of the country, he was a productive author who had written novels about the countryside and created full descriptions of the rural life, he was an experienced translator of Serbian and Bulgarian folk poetry. He also intended to translate Russian and Estonian poetry, but these projects were not carried out partly because of his translations of Finnish poetry.

Holeček was very passionate about the translation of the Kalevala. He learned the Finnish language on his own through his love for poetry and he used German grammar books as support and these were difficult to obtain. Although Holeček had read the German and Russian translations of the Kalevala, he managed to create a completely independent translation. Furthermore, he published his translations of both the Kalevala and the Kanteletar at his own expense.

Despite the fact that Holeček learned Finnish on his own and he did not yet have access to very many Kalevala reviews or close connections to Finland (except for the Slavist Jooseppi Julius Mikkola, who was a friend of Holeček and who reviewed the translation), the Czech version of the Kalevala, the result of twenty years of work, was incredibly true to the original book. The differences between the original and the translation – in the Czech version of the Kalevala the verses are not as much combined to each other as in the original version, but it is more adorned, explicit, vivid and rich in its concrete descriptions – stem from the differences of the languages. First of all, in the Czech language there are, roughly speaking, no verses that are alliterations, and therefore, Holeček had to use lexical rhymes (compare this to the grammatical rhymes and how the vowels follow each other in the Kalevala by Lönnrot). Secondly, the conjugation in the Czech language leaves more room in the verse, whereas in the Finnish language the words are long as a result of agglutination. Holeček filled the space, that appeared because of this, in his translation mostly by extra adjectives or adverbs.

Holeček had exceptional poetic talent and his sense of language was impeccable. His translation of the Kalevala is, by far, the best Czech translation of the epic. Despite this, other translation have made the Kalevala into an important part of the Czech culture and literature. For example the following are worth mentioning: The translation by Bořivoj Prusík (1908) of E. Granström’s prose version of the Kalevala (1881); Josef Honzlʼs Severské báje a pověsti: Kalevala (Pohjoisen myytit ja kansantarut: Kalevala 1941, in English: The Northern myths and folk tales: the Kalevala), was planned as a prose adaptation; the prose story by Bohuslav Čepelák Severské báje a pověsti (Pohjoisen myytit ja kansantarut, 1946, in English: The Northern myths and folk tales: the Kalevala) and the book by Vladislav Stanovský O třech bratřích z Kalevaly a kouzelném mlýnku Sampo (Kolmesta Kalevalan veljeksestä ja ihmeellisestä Sampo-myllystä, 1962, in English: About the three borthers in the Kalevala and the miraculous Sampo-mill), a prose translation with a few short excerpts of the poems written in Kalevala poetic meter. All translations that have been done in the 20th century were for young readers.

Author: Jan Čermák