Lâle and Muammar Obuz 1965

The first part of the Kalevala by Lâle and Muammar Obuz was published in 1965.

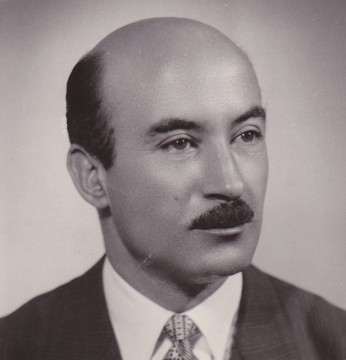

Muammar Obuz was a lawyer who became a politician in 1946 and from 1961 he worked as a senator. Mrs Lâle Obuz was born in Heinjoki, in the part of Karelia that Finland had to give up to Russia. Her birth name was Liisa Partanen. Muammar Obuz had visited Finland for the first time in 1954 and during this visit he had learned to know both Miss Partanen and the Kalevala.

Paul Jyrkänkallio summarises: “Thankfully, Mrs Obuz was the sort of Finn who not only loved and respected the Kalevala, but who reads it over and over again. Thus, the Kalevala was packed in her belongings when she moved to Turkiye in 1957, where the couple got married”.

The work with translating the Kalevala into Turkish started in 1963 when Liisa, who had changed her name to the Turkish name Lâle, had learned the language of her new home country to a sufficient extent. At first, the Obuzs translated the text word-by-word and only after this they created the final Turkish translation. The first part of the translation is from 1965 and it contains the poems 1–25. The second part, the poems 26–50, came out as soon as the following year. The translated poems were abridged and, according to Jyrkänmäki, the amount of verses were, on average, reduced by one fifth. There is an appendix containing an introduction to the history of Finland, a chapter on the origin of the Kalevala and a short biography of Lönnrot. Unfortunately, these texts include misunderstandings.

“The senator and Mrs Obuz have been aware of the difficulties of the task”, Paul Jyrkänkallio writes. “They have done the work all by themselves and they have not asked for help from Finland where, I am sure, the Kalevala Society and the authorities would have been ready to give all sort of support, for example by acquiring books with comments on the Kalevala and translations that have been published in other languages. The translators have added a list of the literature that they have used to their preface. This list shows that they have not had access to many important books. This aspect has not only made the work with the translation more difficult, but it has, undoubtedly, caused some of the misunderstandings.”

The translation is, for the most part, a word-by-word translation. However, the translators have attempted, to some extent, to use the same number of syllables as in the Kalevala and they have tried to create a rhythm with the help of a deviating structure of the words in the phrases. Jyrkänkallio says that because of the clear structure and powerful grammatical suffixes in the Turkish language “there are, at some point, beautiful end rhymes, when the verses intuitively submit to a coherent poetic meter. However, there are no alliterations.”

The translators have consistently used simple loanwords with Persian and Arabic origin, if possible, avoiding the distinctive Turkish vocabulary. Because of this, the text is clear and exact, almost monumental and naturally archaic without any impression of it being artificial. At its best, the result is a poem that has the feeling of originality and, at the same time, is close to the atmosphere of the Kalevala.”

The Turkish readers who reviewed the translation, particularly praised the poems 1 and 19–25. Muammar Obuz thought that the reason for the positive response was the general feeling of humanity in the topics of those poems and the emotions that were explored in them. In particular, the wedding poems are very similar to Turkish wedding poems.

The translators themselves present the following example of, in their opinion, the best Turkish translation, which is poem number 4. However, it is interpreted in an exceptionally free form. The ending of the lament by Aino’s mother is translated as follows:

| The 4th poem in the Kalevala | Turkish (Obuz & Obuz) | Finnish (Jyrkänkallio) |

| Niin emo sanoiksi virkki kuunnellessansa käkeä: ”Elköhön emo poloinen kauan kuunnelko käkeä! Kun käki kukahtelevi, niin syän sykähtelevi, itku silmähän tulevi, ve’et poskille valuvi, hereämmät herne-aarta, paksummat pavun jyveä: kyynärän ikä kuluvi, vaaksan varsi vanhenevi, koko ruumis runnahtavi kuultua kevätkäkösen.” |

Yavrusu yok olan ana Kuş sesi dinlemesin, Bu ses duyulunca, Kalp çarpar, yaş boşanir Gözlerden yanaklara Nohut, nohut! Bu ses duyulunca Kalp çarpar, ömür kisalir Arşin, arşin! Bu ses duyulunca, Kalp çarpar, ana yaklaşir Kariş, kariş!Ölüme ulaşir. |

Lapsukaista vailla oleva äiti Älköön kuunnelko linnun ääntä. Taman äänen kuuluessa Sydän lyö, kyyneleet virtaavat Silmistä poskille Pienoisten herneiden tavoin. Taman äänen kuuluessa Sydän lyö, ikä kuluvi Kyynärän verran. Tämän äänen kuuluessa Sydän lyö, äiti lähestyy Vaaksan verran Kohti kuolemaa. |

Jyrkänkallio, Paul: ”Kalevalan turkkilainen käännös” – Kalevalaseuran vuosikirja 46. Helsinki: WSOY. 1966.