Mercedeh Khadivar Mohseni ja Mahmoud Amir-Yar-Ahmadi 1999 ja 2022

Mercedeh Khadivar Mohseni.

Mercedeh Khadivar Mohseni, in May in 2016:

“I came to Finland originally to study art history. We moved from Iran in 1984 with my husband who had graduated with a licentiate degree in technology. In Helsinki, during my art studies, I first got acquainted with the Kalevala when I studied the breathtaking paintings by Akseli Gallen-Kallela at the Ateneum. It was then I learned to understand the Finnish mythology that the paintings were based on. The world of the Kalevala opened up to me more in depth when I had read the whole epic in Finnish in 1993.

When my husband and I explored the contents of the Kalevala more thoroughly and the motives that Lönnrot had, we were amazed by the similarities between Lönnrot’s groundwork and Ferdowsi’s work (Shahnamen, in other words the author of the national epic of Iran). Ferdowsi (appr. 940–1020 AD) was a Persian poet, who through his poetic epic tale revived the Persian language and culture, which had been suppressed by the Arabs.

Mahmoud Amir-Yar-Ahmadi.

Our respect towards Lönnrot’s life’s work reached new heights when we realised its importance from the point of view of the Finnish language, culture and national identity in the atmosphere that was predominate in the 19th century. We wondered about the fact that the Kalevala had not been translated into Persian! A language, that is spoken by approximately one hundred million people in the world, not only in Iran, but also in Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and today also by a significant minority in many countries in Europe.

Translating the Kalevala into Persian became our mission and our dream and we were determined to make this come true. We wanted to become cultural messengers.

It is not possible to translate a national epic in a poetic form without understanding that you have to be both humble and altruistic. My husband and I decided that we would be completely committed to this project and that we would not under any circumstance try to make any simplifications and give up on the high standards that we had set for the project. We translated the text directly from Finnish to Persian. We did not read any material in other languages and we did not use any as a reference. We were determined to use the Kalevala meter and strive for an exact translation and avoid paraphrasing, using synonyms or – first and foremost – using loanwords from other languages, for example, from the Arabic language. We did not want to compose prose or any other fairy tale based on the Kalevala from our own imagination.

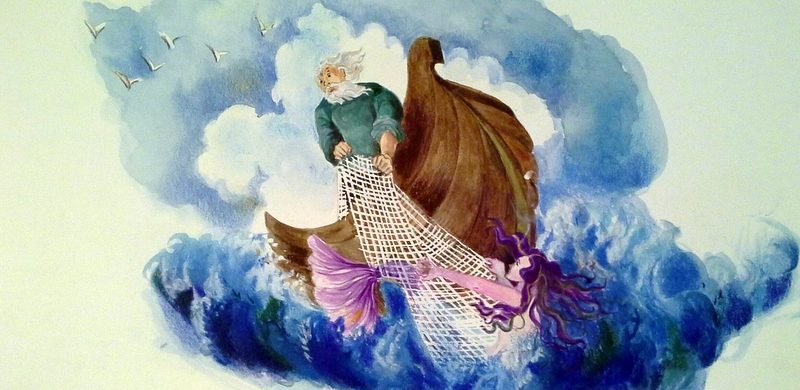

Mercedeh Khadivar Mohseni illustrated the Persian Kalevala. Here is an illustration of the poem number five, where Väinämöinen is looking for Aino in the sea and catches her as a fish in the boat.

Finnish is a colourful language. While we were working, we were also amazed by the richness of the Persian language. In the end, we managed to find a Persian equivalent or translation to each character, animal, weather phenomenon, tool, even for the proper nouns, that appeared in the Kalevala. This was a very hard phase in our work but at the same time very rewarding.

There are many loanwords in modern Finnish that are of an Indo-Iranian origin. It is fascinating to see how many word pairs there are in two languages that are spoken in completely different parts of the world and how these word pairs are either completely or almost completely identical when it comes to their meaning and phonetic form. Maybe this can be explained by the interactions between the Finno-Ugric and Indo-Iranian languages that took place thousands of years ago. The tribes that spoke the languages have most likely lived close to and in perfect peace with one another. We made a list with examples of the similar word pairs that we found.

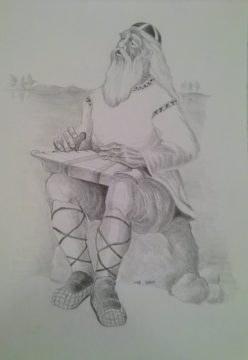

Drawing by Mercedeh Khadivar Mohseni of Väinämöinen playing a kantele he built from a pike jawbone.

At times I was so deep in my thoughts and in the world of the Kalevala that I felt that I could imagine myself wandering and breathing in the mystical surroundings of the Kalevala. Along with the translation work, I was inspired to make illustrations of some of the significant scenes in the book.

When the translation was done, the first edition was published in Iran in 1999. It was exceptionally well received. We are very happy that the book can be found in libraries and in schools all over the world. During the project, we received a lot of support from the Kalevala Society and we want to express our gratitude to the dedicated and professional staff and members of the Society.

The Kalevala has become an indelible part of our life. We have planned to publish the Persian Kalevala as an ebook to make it even more accessible. We have also worked on an illustrated Kalevala for young readers and this book is practically ready for publication. Our goal is that this book should also be available as an ebook.”

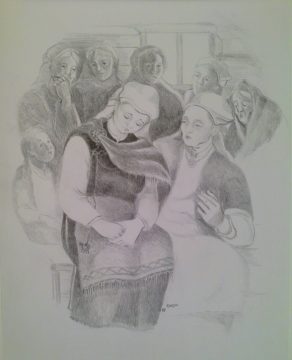

Mercedeh Khadivar Mohseni’s illustration for the wedding poems in the Kalevala.

List of words

The Persian time period from which the similarities of the words originates have been marked on the list. The Avestan language is the oldest known Iranian scriptural language. The Avestan is comparable to the old Persian language. Pahlavi, or Middle Persian, is the name used for the historical transitional form of the combination of Old Persian and Modern Persian. Some of the words on the list are still used in Modern Persian.

saasta – saasta (Avestan or Old Persian), = filth, dirt

sarvi – saru (Pahlavi or Middle Persian), = horn

hyvä – hyv (Avestan), xuup, xvap (Pahlavi), xub (Modern Persian), = good

saraja – zarayah (Avestan), drayap (Pahlavi), darya (Modern Persian), = shed, hut, shack

käärme – kärm (Pahlavi), = snake

jää – aexa (Avestan), yäx, = ice

hame – yaamak (Pahlavi), jaame (Modern Persian), also daman (Modern Persian), = skirt

parvi – parvaare (Modern Persian), = flock, swarm

huume – haoma (Pahlavi), = drug, narcotic

pala – paarak (Pahlavi), = piece

mehiläinen – mägäs-ängäbin, = bee

murkku – mur (Pahlavi), short for ant (muurahainen)

perhonen – parvaane, = butterfly

nokka – nwk (Pahlavi), nok (Modern Persian), = bill, nose

marras – märg (Pahlavi, Modern Persian), = death

minä – män (Modern Persian), = I

me – ma (Modern Persian), = we

sata – sat, = hundred

yksi – aeva, aivaka (Pahlavi), yak (Modern Persian), = one

kude – puud, = weft, textile

puoli – pahluuk (Pahlavi), pahlu (Modern Persian), = half

tappara – tabrak (Pahlavi), täbär (Modern Persian), = axe, hatchet

maamo – maam, = poetic word for mother

tytär – duxt-är, = daughter

kuja – kooiik (Pahlavi), kuy (Modern Persian), = alley, lane

tuore – tärr (Pahlavi), tär (Modern Persian), = fresh

koti – katak (Pahlavi), käd, käde (Modern Persian), home

A second edition of the Persian translation came out in 2022. It can be ordered from the bookstore Books on Demand.