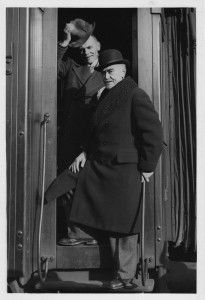

Paolo Emilio Pavolini 1910

The philologist and linguist Paolo Emilio Pavolini (1864–1942) was a professor of Sanskrit at the university in Florence and an eminent researcher and translator in Italy. He translated Estonian, Polish, Albanian and modern Greek literature and poetry and also a part of the Indian works Rāmāyana and Mahābhārata. In 1902 he published an interesting article on the Estonian national epic the Kalevipoeg, which also included a few translations of the work. In his article, Pavolini also compares the creative process of the Kalevipoeg and the Kalevala. He notes that Friedrich Reinhold Kreutzwald first collected prose stories, which he transformed into poems when he wrote the Kalevipoeg. Pavolini was not happy with the fact that Kreutzwald had burned all the original stories and his own manuscripts. On the other hand, Pavolini had great respect for Lönnrot, because Lönnrot had kept all the folk poems that he had collected.

Pavolini began working on his own translation of the Kalevala in 1903 and he used it as an exercise for his studies in the Finnish language in the same way as Cocchi. In the following year he made a trip to Finland in order to learn the language and culture of the country. Emil Nestor Setälä – an influential Finnish linguist and folklorist – was his guide and together they travelled to the Äimäjärvi in Ladoga Karelia. During his visit Pavolini got to listen to the poetic songs about the feasts in Pohjola, the creation of the world, the Great Oak, the singing matches and the death of Christ. During his travels Pavolini also learned to know and became friends with professor Kaarle Krohn. Pavolini translated Krohn’s version of the singing match into Italian, which resembled the version that Härkönen had performed with.

From prose to poem

Setälä and Krohn encouraged Pavolini to continue the translation of the Kalevala, a work he had started as a prose version. However, after his trip to Finland Pavolini was amazed by how easy and natural it was for him to translate the verses also according to a trochaic octameter, a form he considered to be most suitable for the epic. The translation was finished by 1907, but it was not published until 1910, a year after Cocchi’s translation. The publisher printed a gorgeous publication as part of the series La Biblioteca dei Popoli, which was led by Giovanni Pascoli.

Pavolini’s translation is considered to be the best translation and most true to the original work. Professor Aarne M. Tallgren (1885–1945) also viewed Pavolini’s translation as the best translation. Pavolini dedicated his translation to Comparetti and defended the trochaic octameter in his foreword. It was, according to him, the typical poetic meter in Finnish folk poetry and its monotonous rhythm stemmed from the original songs. Compared to the hendecasyllabic meter the octameter is shorter and thus, typical for many of the folk poems. A short meter is also used in the Icelandic Edda and in the Serbian epics.

Maternal emotions and magical words are more important than the war

Pavolini’s opinions on the poems of the Kalevala differed to a great extent from Cocchi’s views. According to Pavolini the poems in the Kalevala were not that ancient and he knew that Lönnrot had removed some Christian content. The tales of war were, in Pavolini’s view, not at all important in the Kalevala. Instead of these tales, Pavolini emphasised the maternal and family-oriented emotions in the work and he pointed out the despair and pain that the mothers of Lemminkäinen and Aino experienced. Pavolini focused his attention on the descriptions of the nature, animals and how the birds talk and guide people and how the swords, boats, the sun and the stars may have suffered, hoped and rejoiced. The poems, in which the home may talk and impatiently wait for the bride, were in Pavolini’s opinion exceptionally good.

Pavolini did not pay much attention to weapons and fights in the world of the Kalevala. He found the magical and creative words, in other words the spells, more important as they helped Väinämöinen to beat Joukahainen, save Lemminkäinen from all the deadly dangers, perform bloodstopping and tackle the freezing cold. Pavolini realised that the singer possesses knowledge and through a song the singer can make flowers bloom on a rocky island, trees grow green and birds come to the branches of the trees.

Vesa Matteo Piludu: “Väinämöisen kyyneleistä tuli Venetsian kaunein tyttö. Kalevala italialaisten kääntäjien ja kulttuurivaikuttajien silmin” – Kalevala maailmalla. Helsinki: SKS. 2012.