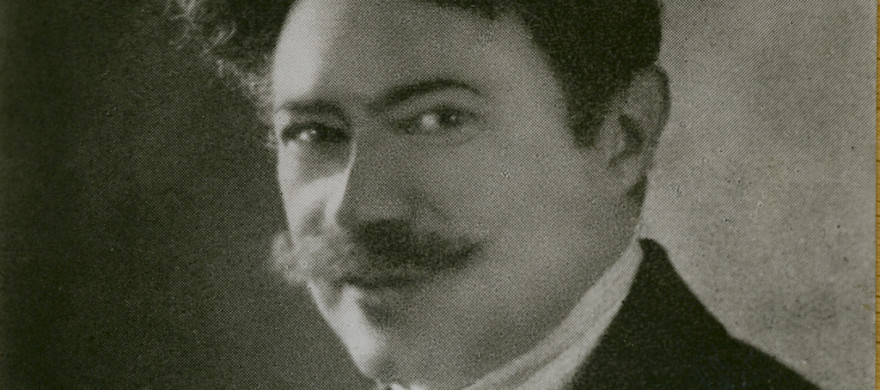

Saul Tschernikovsky, 1930

Saul Tschernikovsky (1875–1943) was originally a Russian-Jewish medical doctor, who became known as a poet, translator and linguist. He was passionately interested in the Hebrew language, which had been restored and renewed, first as a written language in the 18th century and as a spoken language in the 20th century. Tschernikovsky translated classics of the world literature into Hebrew, for example, Homer, Platon, Goethe, Shakespeare and Longfellow’s The Song of Hiawatha.

Saul Tschernikovsky studied to become a doctor in Heidelberg and started working as a doctor in St. Petersburg. He visited Finland for the first time in 1912, while he was on a holiday trip in Metsola in Karelian Isthmus (the stretch of land between the Gulf of Finland and lake Lagoda). Tschernikovsky fell in love with the nature in eastern Finland and was interested in the Kalevala, of which he read Belskij’s Russian translation.

Besides Hebrew, Tschernikovsky also knew the most important European languages, in other words Greek and Latin. However, he did not know Finnish and thus, when he started to translate the Kalevala into Hebrew, he translated Belskij’s Russian version.

He started his work with the translation in 1917. In 1922 Tschernikovsky moved via Turku to Berlin, where he completed the translation in 1924. It took six years before a publisher took on the Hebrew Kalevala and published it. A Finnish businessman David (Dave) Morduch was really excited about the translation and arranged funding for it. The Kalevala in Hebrew was published in Berlin in 1930.

According to Aino Hentinen the result was “an abridged abridgment”: it consists of 29 chapters (Belskij’s version had 50), the Aino-poems are completely missing, as well as Kullervo’s revenge and death. The poems 22–23 have been left out. However, the central occurrences and the heroic stories are conveyed to the Hebrew readers.

Finland’s kantele and Sion’s kinnor

At the centenary of the Kalevala in 1935 Saul Tschernikovsky talked about what the Kalevala and its Hebrew translation meant to him:

“I am happy and honoured to have been invited here to tell you, together with representatives of people from several countries, about our admiration for and thankfulness to the noble Finnish people who have been wise enough to loyally preserve these gems throughout the millenniums, which were created in ancient times by its spirit. I am happy that I was allowed to forward the wonderful poems of the people who create myths to another group of people who create poems, in other words to the people of Judah, to plant the wondrous flowers from the land of the thousand lakes in the rocky soil in the land of the burning sun.

During this heavy and chaotic time, after the horrific war, a war that humanity has never experienced before, poetry and especially myths, this ancient source of human creativity that defies powers, is almost the only place where people again can meet each other as human beings.

Long live the sound from Finland’s kantele and Sion’s kinnor!”

Aino Hentinen: “Saul Tschernikovsky ja Kalevalan hepreannos” – Kalevalaseuran vuosikirja 34. Helsinki: WSOY. 1954.

Ulkomaisten kutsuvieraiden tervehdykset – Kalevalaseuran vuosikirja 16. Helsinki: WSOY. 1936.

קאלוואלה

מאת: אליאס לנרוט

(תרגום: שאול טשרניחובסקי (מפינית