Béla Vikár: “An illustration project of the Kalevala”

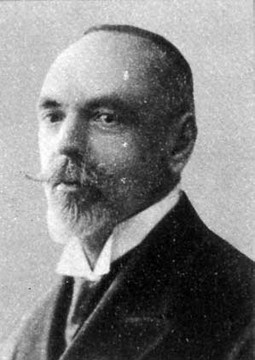

The Hungarian translator, Béla Vikár (1859–1945), writes in his article “An illustration project” (1928) about the process with arranging for the illustrations for the new Hungarian translation of the Kalevala.

Vikár had begun working on a new Hungarian translation of the Kalevala, because the earlier translation by Ferdinand Barna “was not enjoyable for the reader, it was created by a linguist and not a poet”. The plan was that the new translation would include illustrations by the court painter of the Russian czar, Michael (Mihály) Zichy. His older brother was Antal Zichy, who was a member of the Hungarian Parliament and the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. Vikár received a letter of recommendation from him for his journey from Hungary to St. Petersburg in June 1889.

Zichy was, at this point of time, at the peak of his fame, Vikár writes.

“The most eminent magazines in Russia competed of him and his name was very renowned in his home country as well. At the czar’s court he was one of the most influential persons. Thus, it was completely natural to think that he would be an outstanding illustrator of the original and the Hungarian Kalevala.

Our famous son spent his summer holidays near St. Petersburg in the Finnish village Lahta. I wrote to him from the Hôtel de France on the Newski Prospekt and asked him for an audience. I received a note that he would very much like to meet with me, that I would only have to send him a message telling him which day I would visit him, so that we could have dinner with our host.

My friend, Vilmos Csécsy, owned the liquor store Tokai that happened to be in our hotel, and he acquired a servant that would deliver a message to Lahta that we would arrive the following day around 5–6 in the afternoon. We arrived, but everyone in the house was astonished: our peasant had not arrived at Zichy’s house. (On our way back, we found him drunk lying on the roadside, sleeping in the moonlight, with my letter in his pocket.) We arrived – Csécsy with his wife – completely unexpectedly. The dinner was a bit late; I do not believe we caused any other trouble. On the contrary, I had a good opportunity to present my thoughts on the Kalevala to the master.”

Béla Vikár gave Zichy the translation of the Kalevala that he, at that point of time, considered to be the best one, the German translation by Anton Schiefner and he presented his ideas to Zichy. Since St. Petersburg was relatively close to Helsinki, Zichy was easily able to study the ethnographic milieu in the Grand Duchy of Finland and the spirit, which is conveyed by our poetic Kalevala”. The ruler had to give his permission, but the men believed that this would not be a problem. Zichy had, for a similar purpose, earlier also been granted some time off from his duties as a court painter: he had brilliantly illustrated the beautiful version of the medieval Georgian epic by Rustaveli.

Michael Zichy liked the idea and started to read the translation by Schiefner. In January, the next year, he confirmed that he was interested in the task “I am enamoured by the beauty of the Kalevala and its rich content, also from an illustrative point of view.” But the czar kept his most important painter busy and Zichy did not manage to get time off from his work at the court.

Also, soon Finland was the object of another attempt of Russification. It was difficult to see to the intellectual interests of Finland in the czar’s court when the politics of the official Moscow were completely against this. This is most likely the reason for why the master who would have liked to work with the Kalevala illustrations was not able to do so.

Also, the “leading men” in Finland – Ahlqvist, Genetz, Jalava, Setälä, Meurman and others – were, indeed, interested in Vikár’s project, but on the other hand, there did not exist an illustrated Kalevala in Finland, and they did not believe that a foreign artist would be able to study the topic thoroughly enough during a few sporadic study visits.

In Béla Vikár’s opinion the fact that also Hungary waited for an illustrated Kalevala gave further emphasis to the illustration project in Finland, which later was implemented by Akseli Gallén-Kallela and his illustrations. “The Hungarian Kalevala was published and financed by our Academy. Another form of the version of the Kullervo episode was published separately and illustrated with pictures by Gallen-Kallela. It was awarded the biggest prize by the Kisfaludy Society, the Árpád Széher translation award.”

Vikár was hopeful for a continued collaboration. The second edition of Vikár’s Hungarian translation of the Kalevala, which was published in 1935, can be regarded as the result of this much awaited collaboration: the illustrations are the same as in the Kalevala Decorated. The court painter of the czar had been replaced by the pioneer of Finnish national art.

Béla Vikár: ”Eräs Kalevalan kuvitushanke” – Kalevalaseuran vuosikirja 8. Helsinki: WSOY. 1928.