Early Italian translations

The first written mention of poetry in the Kalevala meter can be found in Giuseppe Acerbi’s (1773–1846) English travelogue. Acerbi was not very popular in Italy, because he was the consul in Egypt for the Austrian-Hungarian Empire in the 19th century and Austria was, at that time, the archenemy of the forces that fought for an independent and united Italy.

While travelling in Finland in 1799, Acerbi made notes of a few folk songs, as for example “Nuku, nuku nurmilintu” and “Jos mun tuttuni tulisi”. He documented the melodies of the songs and composed, inspired by these songs, the first chamber music piece that was based on poetry in the Kalevala meter. You can sometimes still hear this piece of music on the Finnish radio.

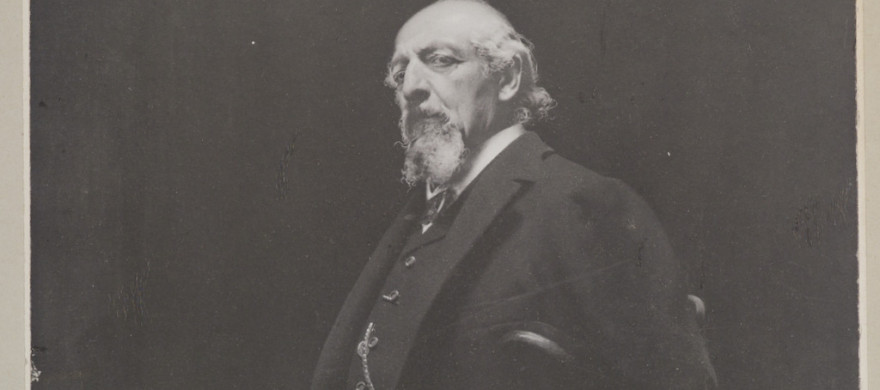

Carlo Cattaneo

After Acerbi Carlo Cattaneo (1801–1869) wrote an article on the Kalevala in 1854. It was published in Milan in a weekly magazine called Il Crepuscolo, which openly showed its support for a united Italy. Like many other national romantics Cattaneo also loved the European epic tales and in 1862 he wrote an article about the epic Os Lusíadas by Luís Vaz de Camões. Later Cattaneo was one of the leaders of the rebellion in Milan in 1848 and he was, consequently, forced to seek exile in Switzerland.

In his article about the Kalevala, Cattaneo praises the melodic form of the Finnish language and he emphasises the importance of the alliteration in the poems in the Kalevala meter. He knew that Elias Lönnrot was collecting folk poetry in the 19th century, but he viewed the contents of the Kalevala to be as old as the epic poetry by Homer. To prove this, Cattaneo compared the Tuonela river with the river Styks in the Aenesi epic by Vergilius, Louhi with the goddess Juno and Sampsa Pellervoinen with the god Saturn. He pointed out that the oak was a holy tree both for the ancient Finnish people and for the Celtics, Romans, Greek and Germans. The antiquity of the poems in the Kalevala was also manifested by the similarities between the forest and water fairies in ancient Greece and Finland.

Cattaneo thought that the “nature poetry” in the Kalevala bore a strong resemblance to the pastoral poems in the ancient Greece and he presumed that the Nordic ancient folk poetry may have had an impact on, for example, the epic Orlando Furioso (1516) by Ludovico Ariosto (1474–1533). It was Cattaneo’s hope that the Kalevala as well as other Finnish oral folk poetry would be translated into the Italian language.

During the time period of the National Romanticism the antiquity of the Kalevala was emphasised in Finland, Italy and in other parts of Europe as well. Cattaneo’s view on National Romanticism was very liberal and openly international. When he compared the Finnish epic poetry to the epic poetry of the Mediterranean region he tried, in his own way, to highlight the cohesion of the people in Europe.

The first translation in Italian of the poems in the Kalevala came out in 1872 when the renowned scholar of the Greek language, professor Antonio Lami, produced a prose translation of a selection of the wedding poems in the Kalevala. These were published in a small book called Dal Kalevala. Frammenti dagli Hää runot o Canti Nuziali. Prima versione italiana. In his foreword, Lami stated that the Kalevala as well as the epic tales in India and by Homer were based on folk poetry from several different time periods and regions. Therefore, the Kalevala was an interesting subject for researchers who studied ancient Greek literature and the “Homeric question”. Elias Lönnrot was regarded as a “living Homer”.

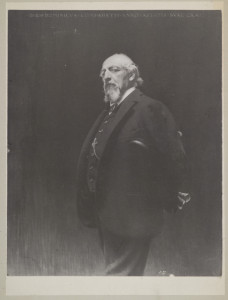

Ottaviano Targioni-Tozzetti

The first Italian poetry translation was published in the same year, in 1872, as a result of the work done by Ottaviano Targioni-Tozzetti. He translated 52 verses of the poem XXVI Kullervon surma (The death of Kullervo) in the Kalevala based on the German poetic translation by Anton Schiefner and the French prose translation by Léouzon Le Duc. Targioni-Tozzetti used the hendecasyllabic poetic meter, in other words Homer’s meter, which was regarded as the best meter for epic poetry in Italy. The translation was published in the journal Il Mare, where Targioni-Tozzetti also wrote a review of the prose translation of Lami’s wedding poem. In this review, he also gave a thorough description of the contents of the Kalevala. Targioni-Tozzetti was a member of the well-known Italian group of authors called the Amici Pedanti. Giosuè Carducci was a poet who received the Nobel prize in literature in 1906 and he was also an active member of the group.

Domenico Comparetti

The first Italian study on the Kalevala was the Il Kalevala o la poesia tradizionale dei Finni: studio storico-critico sulle origini delle grandi epopee nazionali by Domenico Comparetti (1835–1927), which was published in 1891. The study includes translations of the folk poems from Borenius’ work Kalevalan toisinnot. In Comparetti’s opinion the Kalevala was above all an epic of spells. According to his view the magical combats of the heroes and their trips to afterlife were of shamanistic origin. The study was translated into German and English and along with these translations the theories by Comparetti and the Kalevala, in general, became known to several European folklore and literature researchers. The Italian translators of the Kalevala were also well acquainted with Comparetti’s studies.

Other translations of the Kalevala were also done by other parties at the same time as Comparetti. In 1877 Italo Pizzi (1849–1920) translated parts of the poems XXXII, XXXIII, XXXV and XXXVI in the Kalevala and these were published with the title Avventure di Kullervo (in English: The Adventures of Kullervo). In 1881, Giovanni Targioni-Tozzetti (1863–1934, the son of Ottaviano Targioni Tozzetti), who wrote opera librettos, published a translation of the poem XXXVII for the wedding book of his friend and in 1890 the author, librarian and Slavicist Domenico Ciàmpoli (1852–1829) translated the poems VIII and L.

Vesa Matteo Piludu: ”Väinämöisen kyyneleistä tuli Venetsian kaunein tyttö. Kalevala italialaisten kääntäjien ja kulttuurivaikuttajien silmin” – Kalevala maailmalla. Helsinki: SKS. 2012.