Kal’evala vienankarjalakši – Kalevala in White Karelian

The epic Kalevala that was composed by Elias Lönnrot is in Finnish, but a large part of the poems, based on which Lönnrot created the Kalevala, is from White Karelia (Vienan Karjala), which is the northernmost part of Karelia in today’s Russia. Several of the epic poems that were central for the Kalevala, were documented in the old villages in the Uhtua region, in other words the villages where the tradition of oral folk poetry was a very focal part of the life in the village. It was decisive for Lönnrot and the different creative phases of his work when he documented and compiled the poems in the Kalevala that he met with, for example, Arhippa Perttunen, Ontrei Malinen and Vaassila Kieleväinen, who were famous folk poetry singers from White Karelia.

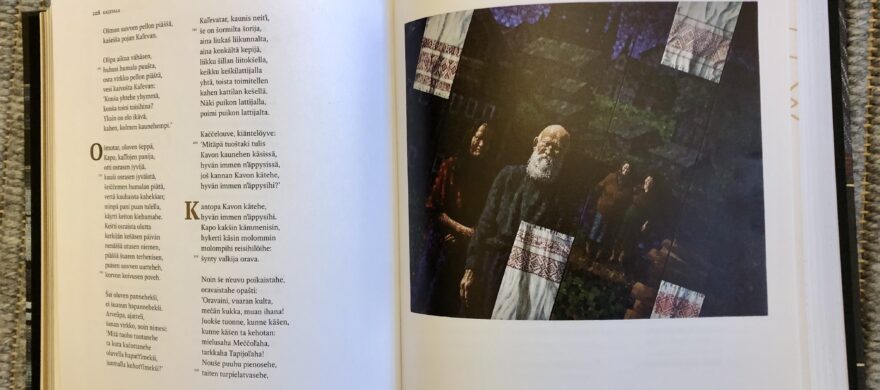

In 2015, a translation of the Kalevala into White Sea Karelian language was published. This translation was done by Raisa Remšujeva (1950–), who is a researcher, translator and journalist. Remšujeva was born at Tollonjoki in the Uhtua region and lives now Petrozavodsk. The beautiful book is illustrated with Kalevala themed paintings by the artist Vitali Dobrini (1950–2021), who also came from the Uhtua region. He was one of the most well-known artists in the Karelian republic.

Challenges with translations

A reader who knows Finnish can read texts in modern White Sea Karelian, but nevertheless, the languages differ from each other to such an extent – and the poetic language of the 19th century was, of course, even more distinct and specific both in Finnish and in White Sea Karelian – that the translator of the Kalevala into the White Sea Karelian language has faced the same challenges as translators who work with other languages. In her foreword ”Kiäntäjän šanat” (in English: Words from the translator), Remšujeva says that it was not easy to translate the texts. The basics, in other words, conveying the contents and format of the poems was, obviously, the first challenge and, besides this, it has also been important to preserve the poetic meter and the alliteration whenever this has been possible. However, Raisa Remšujeva was able to get support from people who speak the languages now as well as from those who have spoken the languages:

”Onnekši rahvahanrunot, kumpasie oli alettu tallentua melkein 200 vuotta takaperin, ta vieläi elävä nykykieli oltih luotettavana apuna.” (In English: Thankfully, the folk poetry that was documented almost 200 years ago and the modern language, that is still spoken, was of reliable help.) “Ne tarittih toičči ušiempieki varianttija” (in English: There were, of course, several versions”, Remšujeva wrote (p. 13).

A translation is done for contemporary readers and the translation into the White Sea Karelian language is no exception from this, as it is a language that is actively used and changing. In order to make the archaic language easily accessible to today’s readers, the translator has strived to lighten and modernise the language of the Kalevala, but on the same time to keep the nature of the poetic language. There is also a White Sea Karelian–Russian special glossary at the end of the book, in order to make it more readable.

- Kal’evala vienankarjalakši. Front cover.

- Kal’evala vienankarjalakši. Beginning of the 1st poem.

Kal’evala vienankarjalakši. Kiäntäjä Raisa Remšujeva. Kuvataiteilija Vitali Dobrinin. Karjalan Šivissyššeura ry. Helsinki 2015.

Timonen, Senni: Lönnrot ja runonlaulun estetiikka. Kalevalan kulttuurihistoria -verkkosivusto. https://kaku.kalevalaseura.fi/lonnrot-ja-runonlaulun-estetiikka/