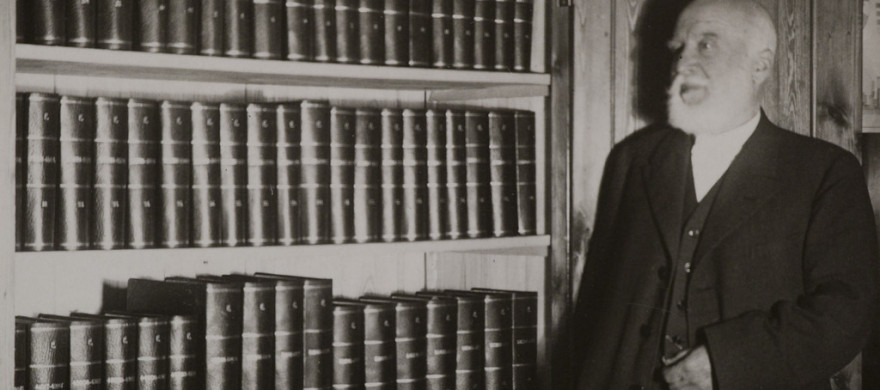

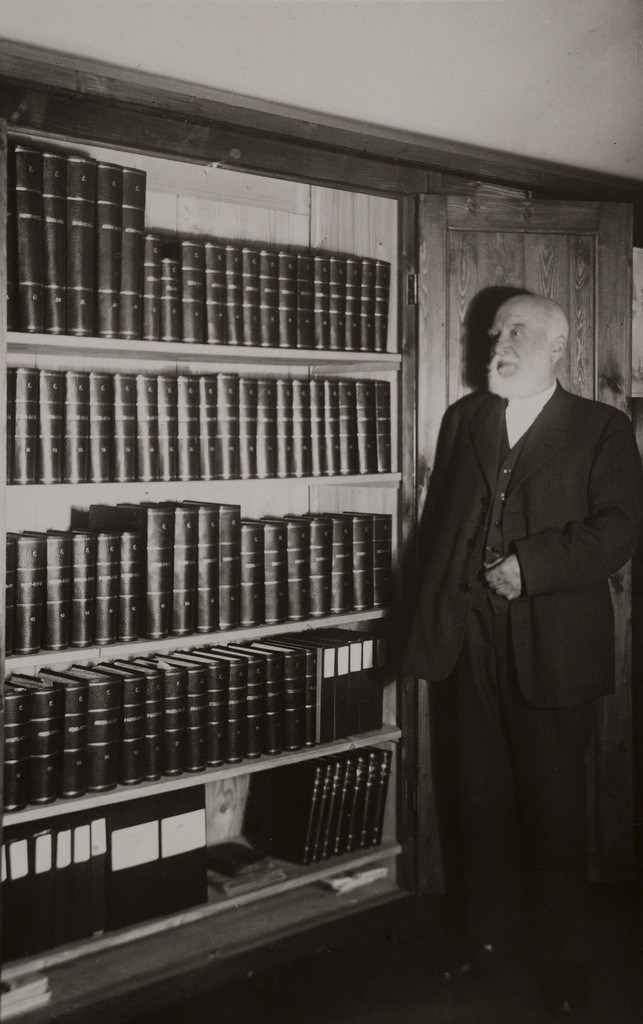

M. J. Eisen 1891 ja 1898

J. (Matthias Johann) Eisen, who was a newly appointed professor at the university in Tarto summarises his views in the yearbook of the Kalevala Society in 1921: “The Finns, the Karelians and the Estonians are the trio that have laid the ground stones for the Kalevala and who have created the Kalevala; their folk poetry is more or less combined with the Kalevala and it is the source from which generations can obtain all sorts of riches”.

Already as a child, M. J. Eisen (1857–1934), was interested in fairy tales and other traditions that were re-told orally both from adults to children an among the children themselves. He became especially interested in folk poetry and, in particular, in the Kalevala when he had graduated from high school and visited the festivities of the Finnish Literature Society in the summer of 1881. During that summer he also wrote a short biography about Elias Lönnrot and started to work on “Pieni Kalevala” (in English: the little Kalevala). It was a word-by-word abridged version in Estonian and it was published in 1883.

J. Eisen worked, in the beginning of his career, as a priest in Inkeri and Aunus. In 1888 he moved to Kronstadt to work there. In the same year, Eesti Üliõpilaste Selts planned on publishing its first album and in connection with this Villem Reiman suggested that Eisen should translate the first poem of the Kalevala according to the poetic meter, since he already had published its content as a word-by-word translation.

“Until then I had not thought of doing a translation using poetic meter. But since Reiman wished for it, I translated the first poem of the Kalevala and I sent it to be published in the album. The further I came with my translation of the first poem, the more interesting I started to find this task, and I became even more enthusiastic about the Kalevala. This made me want to translate more of the Kalevala.”

“The Kalevala forced me to continue”, Eisen describes the process. A plan to translate the complete Kalevala began to emerge, but it was intimidating because of its massive extent. When the Society of Estonian Literati promised to provide funding for the translation, Eisen started to work on it. He did the translation using the poetic meter that had been used in the Estonian translation of the Kalevala. In 1891, the first Estonian translation of the Kalevala, consisting of 25 poems, was published, but although another 25 poems were translated, they were left to wait in order to see how well the first part would sell. But soon after it had been published, the whole Society of Estonian Literati was terminated.

The process of publishing the second part of the Estonian translation of the Kalevala by M. J. Eisen seemed unlikely to be implemented for a long time, Eisen writes. “Finally, in 1898 Eesti Üliõpilaste Selts asked if they could print the other half of the Kalevala. The association provided the funding for the second half of the Kalevala, the poems 26–50, in this year. When it comes to the compensation, I am equal to the father of the Kalevala, Lönnrot: 50 copies and nothing else.”

There were re-prints of the first and the second parts as the first editions were sold out. Eisen revised and corrected his translation for the later editions. In the second edition of the second part, he also changed the poetic meter to the original trochaic tetrameter of the Kalevala.

When M. J. Eisen worked as a teacher at the university in Tarto, Estonia gained its independence and the Kalevala started to evoke interest also in that sense. At the department of the Estonian language, Kalevala became a “lecture and degree subject” for students who studied to became middle school teachers. As a result of this, knowledge about the Kalevala spread among the Estonian people.

“As my interest in the Kalevala has grown during the years, I also hoped that it would grow among the Estonians, especially since, after Estonia became independent, the schools have also started to focus on folk poetry and teach about the Kalevala. I am sure that this focus will lead to results. It has also been pointed out that the most important ingredients of folk poetry, that are less known to modern generations, will again soon emerge into the public eye and the society as well.”

M. J. Eisen: “Miten minusta tuli kansanrunouden kerääjä ja Kalevalan harrastaja” – Kalevalaseuran vuosikirja 1. Helsinki: Otava. 1921.