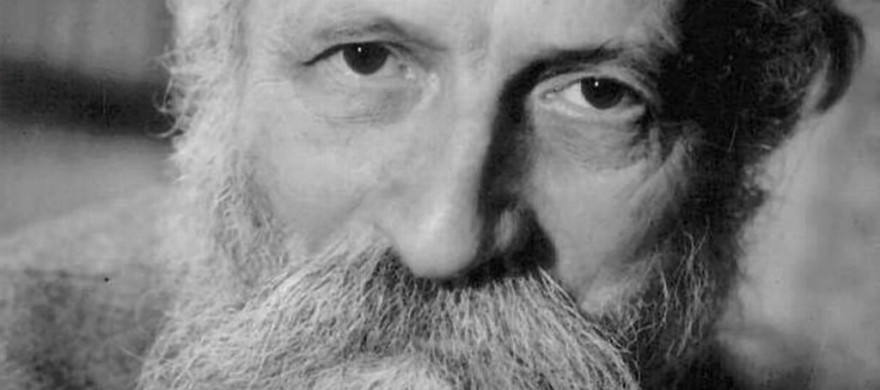

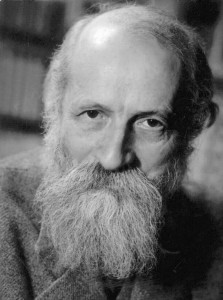

Martin Buber 1914 and 1921

Martin Buber (1878–1965) was born in Vienna. His family was Orthodox Jewish. He is best known as a scholar within the field of social philosophy and he moved from the national socialistic Germany to Jerusalem in the 1930’s, where he continued his work at the Hebrew University.

In the 1910’s Buber became interested in the mythologies of different nations and he started to translate them into German. He did not actually translate the Kalevala, but he made improvements to the translation by Anton Schiefner, whom he admired very much. He even made these improvements twice. According to Erich Kunze, Buber had first considered that he would use the French version by Léouzon le Duc and the English translation by William Forsell Kirby as sources for his translation. However, he came to the conclusion that in comparison to the other German translations, Schiefner had managed to capture the essence of the Finnish epic, something that the version by the linguist Hermann Paul (1885) completely lacked.

Martin Buber was very talented when it came to learning languages and he also studied Finnish in order to be able to read the Kalevala in its original language. None of the previous German translators of the epic had done this before.

Buber wrote in his letter to Erich Kunze something about the motives and progress of his project:

“When I was young, I was guided to read the Kalevala through my research of cosmogonic ancient legends. I was captivated by Schiefner’s translation and the authenticity of its tone; whereas the translation by Paul gives the reader a totally false picture. I decided to publish the book again in 1911 but, at that point of time, I had no plans to make any alterations in it. However, I was quite quickly convinced that some corrections had to be made. I thought that many of the archaic turns of events disrupted the magnificent poetic flow. Nevertheless, it was obvious that I could not correct it arbitrarily and, therefore, I acquired the original book, a book on grammar and a dictionary. By the year 1913 I had come so far that I was able to compare everything; I did the work in the summer of 1913. I had to ask for help from experts because of a couple of difficult passages, but I cannot remember exactly the details of these. I soon realised that it was possible to present several passages, not only in a poetically more correct way, but also more precise than Schiefner. I still think back at this work with great pleasure. I have not added anything else than the epilogue…”

It turned out that both the clarifications and the stylistic modifications that Buber had done in the translation as well as the insightful epilogue, which became a foreword in later editions, made the Kalevala more approachable for the German readers.

In the epilogue, Martin Buber characterises the Kalevala as follows:

“One has to regard a Finnish folk poem as the creative power that the poem has, which is based on beliefs. A poem in the form of a spell is proof of this power, the epic song is a tale of its greatness and the glorification of it. The song praises itself by describing its own power. But the play does not become complete, until the poetic spell is sung. Usually, the singers only refer to the poetic spells, and Lönnrot is the first person that, in fact, has created an epic poem of them. By combining these both, the Kalevala presents the Finnish mythos of the Sage, completes the Finnish folk song. In other words, it becomes the epic of the creative word.”

Erich Kunze: ”Martin Buber ja Kalevala” – Kalevalaseuran vuosikirja 34. Helsinki: WSOY. 1954.