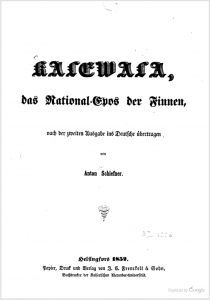

Anton Schiefner 1852

Anton Schiefner, who was a member of The Saint Petersburg Academy of Sciences, was the first one who made a complete translation of the New Kalevala in poetic meter. The translation was published in Helsinki three years after the book had been published in Finland for the first time, in 1852. However, the book was not translated into Russian but into German.

Schiefner was a linguist and a renowned researcher in Fenno-Ugric languages. He was born in Reval, in other words in Tallinn, but he worked mainly in St. Petersburg.

In his letter to Elias Lönnrot (March 29, 1848) he wrote about how he became interested in the Kalevala:

“When I went to school in Reval (in Finnish Rääveli that is now known as Tallinn), I found the history of the Homeric songs extremely fascinating. I have since then not been able to forget my love for the epic story. I read about something called the Kalevala for the first time in the information leaflet ‘Mittheilungen der estnischen Gesellschaft zu Dorpat’ and, if I remember correctly, I also read something at the same time in the magazine ‘Journal des Ministerii der Volksaufklärung’. When I was in Germany (1840–42) I studied in Berlin, under the guidance of Lachmann, the Song of the Nibelungs and I was still thinking of this when I found the translation of the Kalevala by Castrén in the summer of 1843. Now I was finally able to learn about the exact content of the single poems. However, it was primarily the article by Jacob Grimm [sic] about the Finnish epic that had such an impact that I started, although late, in other words during the summer, to work on the original [Kalevala].”

Schiefner translated the Kalevala from Finnish to German. He used Renvall’s dictionary and the Swedish translation by M. A. Castrén to help him with the translation. Castrén sent Schiefner prints of the New Kalevala directly from the book printing company, even before the complete book had come out. This explains how it was possible that the translation was published so quickly.

Schiefner did not alter the Kalevala poetic meter. Here he followed the way Castrén had done the translation and the principles that prevailed during the romanticism, according to which the translation should be as true to the source text as possible.

However, this was criticised by both Finnish and German scientists. In particular, August Ahlqvist (1826–1889) was critical to this. Professor Wilhelm Schott (1802–1889), who was a researcher in oriental languages, and who would have liked to translate the Kalevala himself, argued against the translation by Schiefner, for example with the following examples:

“[…] verse 474–478: ’Kun lie näissä voitehissa Wian päälle vietävätä, Wammoille valettavata’ etc, word-by word [in German]: ’wenn sein sollte in diesen Salben auf den Schaden zu bringendes, auf die Verletzungen zu giessendes’, in other words, if this ointment can be used on a wound, spread on something damaged… Schiefner, on the other hand in contrast to the obvious meaning of the text and, furthermore, hideously, unlyrically: Dadurch (!), dass mit dieser Salbe Ich den wunden Fleck bestreiche, Ich den Bruch damit verschmiere […] Poem 11, verses 87–92. Here, Mr Schiefner makes the tactful Lemminkäinen say the following threat that is as tasteless as it is preposterous: ’Werd´ der Weiber Lachen hemmen, Werd´ der Mädchen Kichern dämpfen, Schlag mit Füssen an den Busen (!), Schlage nach den Arm des Säuglings (!!!); Das beendigt wol das Schmähen, Ist ein guter Schluss des Spottens’. Now there we have a fantastic hero who kicks girls in the chest with his feet and hits babies on their small hands! Mr Translator must have peculiar ideas about the requirements for a knight.” (Schott 1857, 117.)

Schott’s summary of the translation by Schiefner was brutal: “But, despite the numerous blunders, this translation is aesthetically insignificant and there is little that bears resemblance to the Homeric simplicity of the original [text] and its luscious richness of nature.”

Even though the translation by Schiefner was not highly valued at the time, it has given important support to German translators. It has also functioned as a work of reference for many translators that have made translations of the Kalevala into other languages.

Liisa Voßshcmidt: “Saksan kautta eurooppalaiselle kulttuuriareenalle” – Kalevala maailmalla. Helsinki: SKS. 2012.

Mirja Kemppinen ja Markku Nieminen: “Rekonstruoidusta kansaneepoksesta Lönnrotin runoelmaksi – Kalevala Venäjällä” – Kalevala maailmalla. Helsinki: SKS. 2012.